So yeah, we’re basically talking about the center of global capital here; Midtown baby!

I was wondering about beginnings the other day: how all these massive businesses or institutions that seem so complicated got their start – you know, finance, communications, utility companies, that kind of thing . Were they all massive and confusing from the get go, or did they all just start in somebody’s garage? (You know, and then through hard work and making sure that government didn’t hamper their drive, potential and confidence with pesky regulation grow into the heroic job creators that they are today?)

Sixth Avenue and 42nd Street is home to the Bank of America Tower – headquarters for the company’s investment banking division. So yeah, lots of global capital probably cruising through the joint, well on computers at least. Forbes listed Bank of America as the 3rd biggest company in the world in 2010. So how did they get their start? I hate to tell you, but it seems like it was basically in somebody’s garage….and by an Italian no less! That’s right, Bank of America was founded as the Bank of Italy by Amadeo Giannini, in San Francisco in 1904. Now sure, he’d made his money as a broker for his step-father’s produce business first and had married the daughter of a North Beach real estate magnate before becoming one of the directors in a bank in which his step-father owned an interest, but Giannini did start his bank in a fashion that springs right from the heart of the American Dream. Though American born himself Giannini realized that few banks catered to immigrants and took advantage of that vacuum to create the Bank of Italy – geared towards the working-class Italians of North Beach. When the earthquake of 1906 hit, Giannini was able to rescue all his deposits – something not every bank, or even close to every bank, was capable of – and a few days later he started making loans to help with the rebuilding of the city, from his makeshift office composed of a plank placed over two wooden barrels. And everyone of those loans was eventually paid back. Now is that story true? Who cares? America! (Bank of) America!

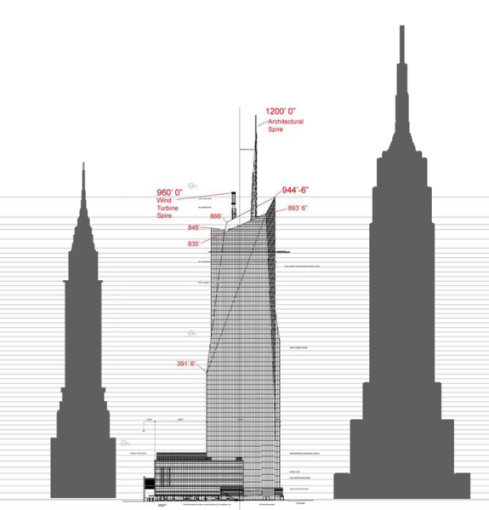

The Bank of America Tower is currently the third highest building in NYC, after the still uncompleted One World Trade Center and the ever-solid Empire State Building – though it really doesn’t look that tall. It’s probably the all-glass facade that masks it vertical grandeur, and the fact that it doesn’t taper off into a spire. Though technically its top does include an “architectural spire” that allows it to reach its official height of 1,200 feet, although to me there’s nothing architectural about it. I’ve never quite understood this height distinction thing in that regard – when a spire counts and when it doesn’t. The Empire State Building is usually listed as a height of 1,250 ft. – but it goes up to 1,454 if you include its antenna spire. But how is that antenna spire any less a piece of architecture than the Bank of America Tower? Who can say? (How many people care?) I guess that I should probably ask the Council on Tall Buildings and Urban Habitat about this kind of thing. They’re the foremost authority on the official height of tall buildings (you know they just added that Urban Habitat to their name to sound like they don’t just care about how tall a building is). These guys really exist, and they apparently have over 450,000 members; if you ever run into one of them at a party stick around.

They gave the Bank of America Tower their Tall Building Americas Award in 2010….so clearly they like the joint. Since the building was completed in 2009 it’s generally received a lot of accolades, mainly for its ecological design. It was the first skyscraper in the world to receive a Platinum LEED (Leadership in Energy and Environmental Design) Certification, and so I’m sure the place is pretty cool. I’d probably think it was cooler if it wasn’t the investment banking division headquarters of a major bank. But shit, why I got to be a hater? Let me do a little more research and I’ll let you know. I’m sure I’ll come up with some reasons.

Well that didn’t stop the Park Row Building from going up, backed by its financiers under the leadership of August Belmont. Belmont would go on to found the Interborough Rapid Transit Company in 1902, the group that brought the first subway lines to Manhattan. The Park Row Building would be their initial headquarters during their fledgling years. Belmont bought the pre-existing Manhattan Railway in 1903, operators of the four elevated railway lines in Manhattan (with one extending up into the Bronx). When his IRT subway lines opened in 1904 the company had a monopoly on rapid transit in New York. They would eventually face some competition from the Brooklyn based, Brooklyn-Manhattan Transit Corporation as well as the city-owned Independent Subway System. That would last until 1940, the year the city forced the take-over of both the IRT and BMT. The IRT’s lines would become the A Division of the subway, and encompass all services designated by a number. The BMT and the Independent’s lines would become the B division – all services designated by a letter.

Well that didn’t stop the Park Row Building from going up, backed by its financiers under the leadership of August Belmont. Belmont would go on to found the Interborough Rapid Transit Company in 1902, the group that brought the first subway lines to Manhattan. The Park Row Building would be their initial headquarters during their fledgling years. Belmont bought the pre-existing Manhattan Railway in 1903, operators of the four elevated railway lines in Manhattan (with one extending up into the Bronx). When his IRT subway lines opened in 1904 the company had a monopoly on rapid transit in New York. They would eventually face some competition from the Brooklyn based, Brooklyn-Manhattan Transit Corporation as well as the city-owned Independent Subway System. That would last until 1940, the year the city forced the take-over of both the IRT and BMT. The IRT’s lines would become the A Division of the subway, and encompass all services designated by a number. The BMT and the Independent’s lines would become the B division – all services designated by a letter.